How did “proof” come to be?

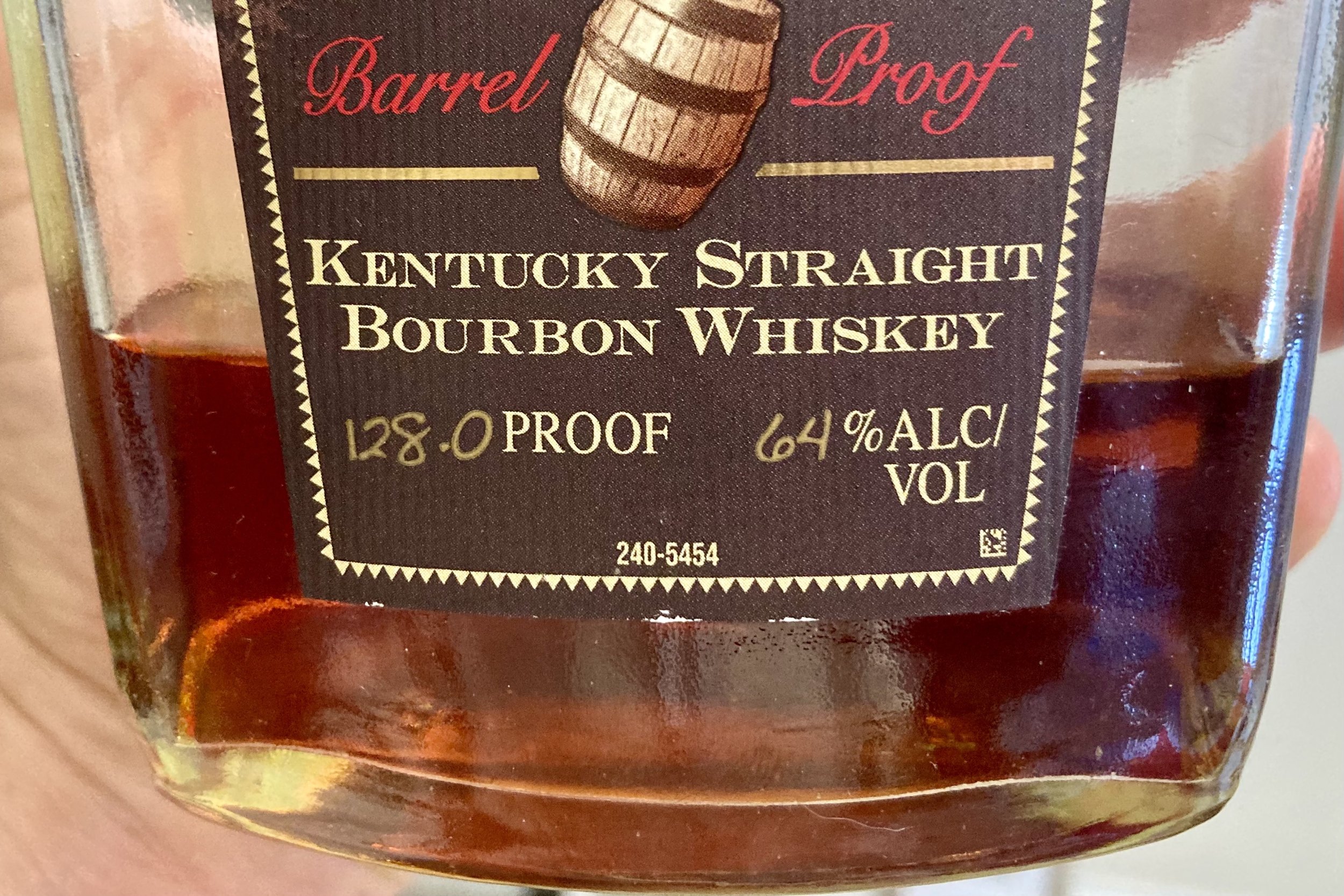

Proof is simply just twice the percent alcohol by volume (ABV). But it seems silly to have both ABV and proof listed on a bottle of distilled spirits. So how did proof come to be?

The development of the term “proof” in reference to alcohol concentration has many stories. Not all of them are historically accurate and I’ve definitely told the more fun ones that may or may not just be myths. Ultimately what it comes down to is taxes. Talking taxes is no fun, so allow me to start with the fun stories!

As it currently stands 100 proof is 50% ABV. But way back in the day, like back during the 16th century, 100 proof was said to be 57.14% ABV. I’ve also seen 57.15%, 57.10% and 57.06% ABV, so in order to cover my bases, I’m going to just call it 57%. But nevertheless what a random percentage! Now as the story goes, sailors of the British Royal Navy were given a daily allowance of booze and this lasted up until July 31st, 1970 by the way. This daily ration was known as the daily tot and beer, wine, brandy and rum were all options depending on where in the ocean the ship was and what was available on board. At some point, the standard tot became rum because the British navy frequented the Caribbean, where rum was produced. This was all a part of the Colonial Slave Trade, which I’m not going to get into right now. It’s said that the sailors would get cranky if they suspected that their rum ration was getting watered down. Maybe it was getting watered down because the crew was too drunk all the time. Nevertheless, the crew didn’t like it. So they would test it. They wanted proof that the rum wasn’t getting watered down. So they would mix some rum with gunpowder and light it. If the gunpowder ignited, that was proof that the rum wasn’t diluted and therefore it was deemed “at proof”. But if it didn’t light, well that would lead to mutiny.

There’s a similar version that says that the sailors needed to have the rum “at proof” just in case it somehow spilled on their gunpowder and they needed to, I don't know, fire some cannons or something. So they would test it as proof that the gunpowder would still light. Regardless of which story you prefer, both ended with, “and at proof, or 100 proof ended up being 57% ABV. Anything less than that and the gunpowder wouldn’t light!”

Now, many factors would impact whether or not gunpowder mixed with rum would ignite other than the ABV such as gunpowder-to-rum ratio and the time of contact of the rum with the gunpowder. So even if this proof test was done, it wouldn’t have had enough reproducibility to claim that 100 proof was 57% ABV. It’s fun to imagine that this technique was used though.

Another story claims that a similar technique was used as a way to tax spirits depending on the alcohol concentration. Here comes the taxes. This was referred to as the burn-or-no-burn test, which is sufficiently straight forward. The booze was lit on fire. If it successfully burned, it was “at proof” and was taxed higher. It was claimed that “at proof” using this method would put the ABV at 57%, but this is easily debunked because the flash point of ethanol/water mixtures is dependent on temperature. This means if it’s a warm day out, a lower ABV spirit will light and if it’s colder out, the ABV would have to be higher in order to ignite. Again, this method is an inaccurate way to determine alcohol concentration.

FYI California state taxes on spirits are dependent on alcohol concentration. Producers owe the state twice as much per gallon if they produce a spirit at 50% ABV or above. So if the burn-or-no-burn test was still used to this day, producers most certainly would wait to file their taxes until the weather was abnormally cold out.

With all of this said, hydrometers have existed for hundreds of years. The Clarke’s hydrometer was invented in 1730 and was the standard hydrometer used specifically for determining the taxation on spirits. Then when the Sikes hydrometer came around in 1816 that became the standard for spirits taxes. With the Sikes hydrometer came the declaration by the British government that a proof spirit would have the density of 12/13 of water at 51 oF, which was, as you might guess, about 57% ABV.

A few years later the French came up with their own very logical scale for proof. Water was 0 proof and ethanol was 100 proof. So 50 proof was actually 50% ABV. This was too logical for the Americans when they began taxing spirits a handful of years later, but the British version was too complicated to use, so they decided to simplify it. And this is where the rule that the proof is twice the ABV comes from. So 100 proof on the American scale is 50 proof on the French scale and 87.5 proof on the British scale.