Meaningless Terms on Whiskey Labels

Whiskey labels are riddled with marketing terms that mean nothing and give us zero indication of what the whiskey tastes like!

Let’s cut straight to the chase. There are so many meaningless words on whiskey labels that just add more confusion to which bottle you should buy. Yes, I will admit, I am drawn to bottles with cool, colorful labels, but it has taken many years of practice to understand what information on the label is meaningful and what is just marketing fluff. These frivolous words don’t give any indication to what the whiskey will actually taste like and as consumers, what we really care about is whether or not we’re going to enjoy the whiskey. So let’s go over them!

Words that hold no meaning on a whiskey label:

Very Old

Extra-aged

Double Matured

Double Wood

Triple Cask

Despite what these phrases intend to suggest, they don’t tell us how long the whiskey was aged or what casks were used to age it. In most cases, whiskey batches are a blend of barrels that have a wide range of ages because each one brings different characteristics to the final batch, which gives it a balanced flavor profile. Most whiskey categories have a minimum age requirement, for example Straight Whiskey in the US must be aged for at least 4 years (without an age statement) and Scotch whisky must be aged for at least 3 years. So we know that a Straight Bourbon Whiskey is at least 4 years old and the batch probably includes barrels that have been aging longer than that. However a “Very Old Straight Bourbon Whiskey” doesn’t tell us whether the barrels in the batch were older than 4 years or not. Similarly, double/triple matured doesn’t indicate whether the whiskey was finished in a second type of barrel or was a combination of two different types of casks in the batch. Each distillery has their own definition for what these terms mean, so it’s difficult to figure out how that changes the final flavor profile.

Small Batch

Very Small Batch

Distiller’s Select

Distiller’s Edition

Vintage

Reserve

Vintage Reserve

Special Reserve

Rarest Vintage Reserve

These words and phrases are intended to make you believe that the bottle you’ve picked up is somehow more exceptional than the rest. However there is no definition regulating how many barrels can go into a small or very small batch. Heaven Hill for example uses around 200 barrels in a batch, while Angel’s Envy uses 8-12 barrels for their batches. Does this mean that smaller batches are better than larger ones? Nope! The only thing we can gather from this is that Heaven Hill has much larger blending vats than Angel’s Envy and again, this means nothing for the final flavor profile. Similarly with words like Vintage, Rare, Reserve or any possible combination of those, doesn’t indicate rarity. Also, Distiller’s Select/Edition does not mean that the distiller was somehow more involved in the whiskey making process than they are for all the other expressions released by the distillery. Again, these phrases don’t give us clues into the whiskey flavor profile.

Sour Mash

Original Sour Mash

Sweet Mash

Double Malt

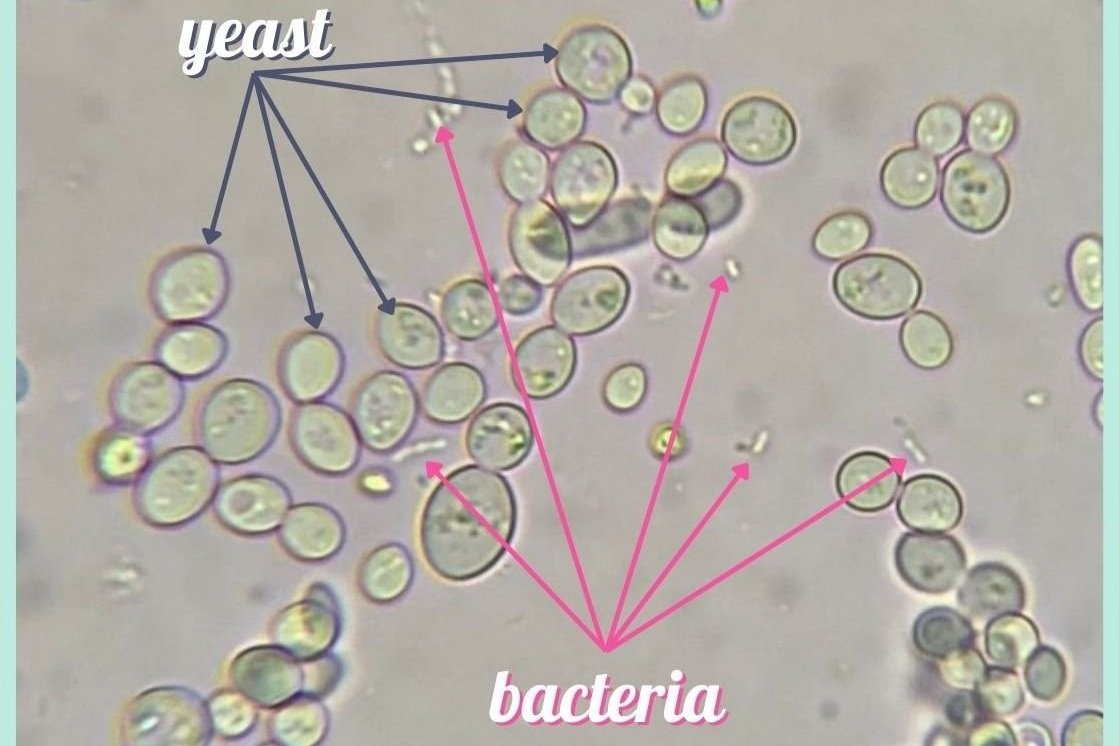

Almost all bourbon distilleries use a sour mash technique, whether they advertise it or not. Some distilleries will indicate if they use sweet mash, which just means they’re not using a sour mash. Sour mashing is when the distiller recycles the stillage (liquid left over in the still after distillation) from one batch to the next. The stillage is slightly acidic, which creates a more optimal environment for the yeast during fermentation and it’s said to keep consistency between batches. This is an interesting thing to know if you’re a bourbon nerd, but in the grand scheme of things, it does not impact the flavor profile of the bourbon. Double Malt is a term that is occasionally used in Blended Malt Scotches to imply that the whisky is a blend of single malts from only two distilleries. I’ve never actually seen this term on a bottle in real life, but it came up during one of the NEAT Blind Tastings. It could possibly give you hints into the whisky flavor profile if it also indicates the two malt distilleries, how each whisky was aged and rough percentages of how much of each whisky went into the blend. Otherwise, the term holds no meaning in Scotland, and therefore doesn’t let us in to what the whisky tastes like.

Craft

Handcrafted

These terms are often used to imply that the whiskey is made in an artisanal way, however they have no legal definition and can be put on any whiskey label. Even ACSA (American Craft Spirits Association) and ADI (American Distilling Institute) have somewhat contrasting definitions for what they consider a craft distiller, but both agree that a craft distillery must be independently-owned and limit their yearly production. In California, a craft distillery holding a Type 74 liquor license is limited to producing no more 100,000 gallons per fiscal year, but it doesn’t have any regulations that require it to be produced in an artisanal way and not every state has a craft distillery license. Still, this doesn’t regulate whether or not a brand can slap the words “craft” or “handcrafted” on their label. I could go on a long tangent discussing the word craft, but I won’t! So yet again, the words handcrafted and craft mean nothing and most importantly, don’t let us know what the whiskey will taste like in the bottle.

I want to end this on a positive note, so let’s talk about words on a label that are useful and significant!

Words that tell you something useful:

Whiskey category (ex: Bourbon Whiskey, Rye Whiskey, Single Malt Scotch Whisky)

This will tell you a lot about the flavor profile of the whiskey based on the regulations that define the production process for the specific category. For example, Highland Single Malt Scotch Whisky is produced in the Highland region of Scotland at one single distillery. The whisky is fermented from 100% malted barley, pot distilled and aged for a minimum of 3 years. It then must be bottled at no less than 40% ABV (80 proof) with only water and caramel coloring added (both are optional).

Regions (ex: Kentucky, Islay, Orkney, Highland)

This will also give you information about the flavor profile based on regional whiskey trends and maturation climates. For example, bourbons produced in Kentucky taste very different from those made in Texas mainly because of the maturation climate. (Note: I know this isn’t the only reason, but it is a major factor.)

Distillery name

Each distillery has their own unique characteristics, so knowing where the whiskey was distilled will tell you a lot about the flavor profile. For example, Caol Ila and Lagavulin use the same peated malt to produce their single malts. However, they taste vastly different because of the stills that they use and distillation cuts that they take.

Age statements

This will indicate the potential oak impact in the whiskey especially for bourbons that are aged in new charred oak barrels.

Alcohol content (% ABV)

This tells you how much alcohol heat you should expect. I will note that really great whiskies, even at high proofs, will have minimal perceived heat.

Cask type(s) for aging and/or finishing

All of the color (unless E150 is added) and most of the flavor in whiskey comes from the oak. What cask was used to mature and finish it is very important in the final flavor profile.

“Non-chill filtered” or “No artificial color”

Neither of these should have a great impact on the flavor profile of the whiskey. Some argue that chill filtering removes some flavor and rich texture in the whiskey, so often non-chill filtering is more desirable. However, non-chill filtered whiskeys have the potential to become cloudy with the addition of water or ice, which isn’t aesthetically pleasing. This is why many distilleries choose to chill filter their whiskeys. Caramel coloring (E150) is not allowed to be added in American whiskeys, but it is common practice in other countries. It’s used to keep consistency in color between batches, but some argue that a few distilleries add too much E150 and that affects the flavor.

“Bottled-in-bond” (USA)

There are very strict regulations for Bottled-in-Bond (BiB) whiskeys. They must be produced by one distiller at one distillery during one distillation season. They must be aged in a federally bonded warehouse (BTW every aging warehouse is bonded now) for at least 4 years and must be bottled at 50% ABV (100 proof). BiB whiskeys are sometimes viewed as higher quality and honestly, I don’t disagree. I like that I know right away that the whiskey is going to be at least 4 years old and that it’s at a higher-than-average proof.You can often find very affordable BiB whiskeys.

“Single barrel/cask” (TTB doesn’t legally define this)

This tells you that there will be slight variations in flavor profile from barrel to barrel and that each one is unique.

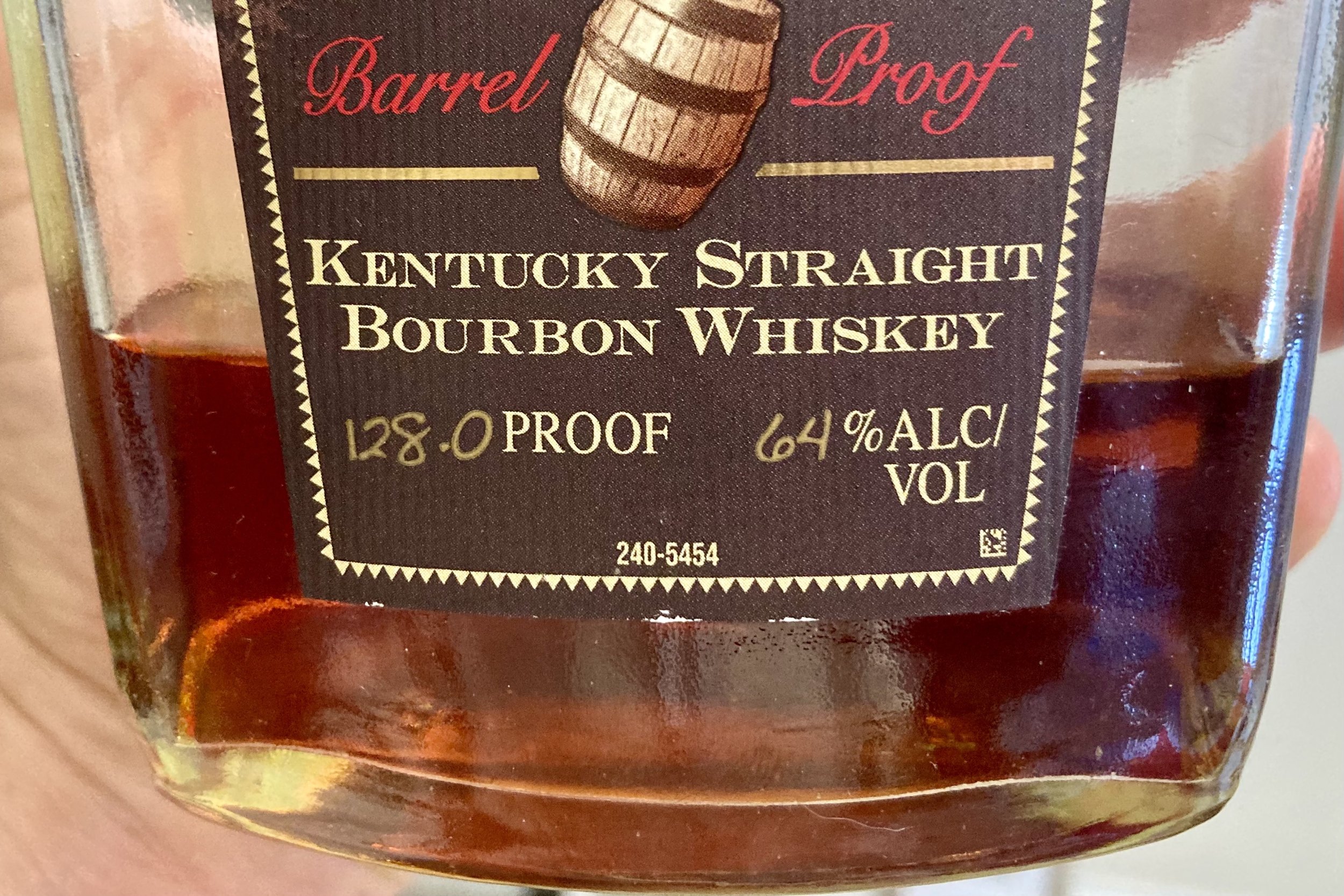

“Cask strength/Barrel proof” (TTB doesn’t define this, so it can be a loose term)

This typically means that little to no water was added prior to bottling. Each distillery defines these terms differently, but usually indicates that the whiskey is packed with flavor because it hasn’t been “watered down”. The bottle will most likely be very high proof, especially in the US.

“Limited release” with bottle number and batch size

This will indicate the rarity of the bottle, but not what it tastes like. Some whiskey bottles will claim that they’re limited releases, but won’t elaborate on what exactly that means. If you’re looking for a whiskey that is truly a limited release, make sure the bottle at least says the batch size.